The Rise of Brain-Computer Interfaces: Enhancing Lives or Invading Privacy?

Non-invasive BCIs are making their way into the consumer market, promising to seamlessly integrate our brains with technology. However, ethical concerns about privacy and personhood loom large.

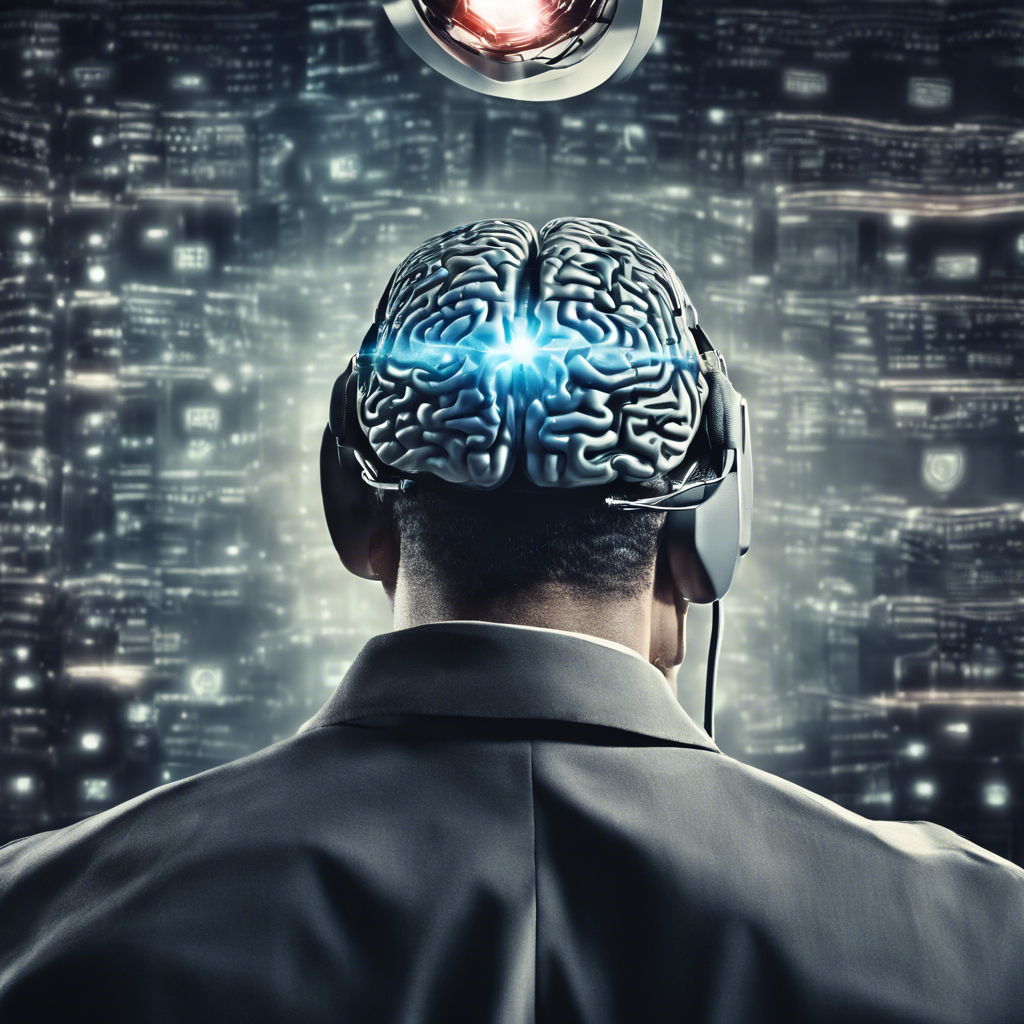

Imagine controlling your computer or smartphone with just the power of your mind. This seemingly futuristic concept is becoming a reality with the advent of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). Startups like AAVAA are leading the charge to bring non-invasive BCIs to the consumer market, offering products such as headbands, AR glasses, and headphones that read brain and facial signals to allow users to control their devices. While BCIs hold immense promise for individuals with disabilities or limited mobility, they also raise important ethical questions about privacy, security, and the blurring boundaries between technology and our very minds.

Work All Day, Sleep All Night:

BCIs showcased at the 2024 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) demonstrated not only the ability to control devices but also their potential to provide insights into users’ health, wellness, and productivity. For instance, the Frenz Brainband measures brainwaves, heart rate, and breathing to curate AI-generated sounds and music to aid in falling asleep. On the other hand, products like the MW75 Neuro headphones from Master and Dynamic use EEG signals to monitor users’ focus levels, potentially perpetuating a culture obsessed with productivity. While these technologies offer convenience and potential benefits, they also underscore the ethical implications of BCIs in a society increasingly driven by work and performance.

An Ethical Minefield:

Unlike invasive BCIs that require surgical implantation, non-invasive BCIs like AAVAA’s headbands and headphones offer accessibility for all users. However, this widespread adoption raises concerns about privacy and data security. The potential access to intimate brain signal data by companies creates unprecedented opportunities for data misuse and discrimination. Privacy issues highlighted in a 2017 review published in BMC Medical Ethics caution against workplace discrimination based on neural signals. While AAVAA assures that they do not have access to individual brain signal data, the concerns surrounding data privacy persist, given past instances of tech companies mishandling user data.

The Question of Personhood:

BCIs also raise questions about the boundaries between humans and technology. As users gain the ability to control devices as an extension of themselves, the question of whether BCIs make individuals less human becomes a topic of ethical debate. Some worry that becoming more robotic may diminish our humanity. Nevertheless, the undeniable benefits of BCIs, particularly for individuals seeking greater autonomy and mobility, cannot be overlooked. BCIs break the limitations imposed by physical disabilities, allowing individuals to control their environment through simple movements of their head or face. The potential for increased independence is groundbreaking.

Conclusion:

The rise of non-invasive BCIs brings both promise and concern. While these technologies offer new possibilities for individuals with disabilities and limited mobility, they also raise important ethical considerations. Privacy, security, and the preservation of our humanity are at stake as BCIs become more prevalent. Striking a balance between the benefits and potential risks of BCIs will be crucial as we navigate the future of this transformative technology. As AAVAA founder Naeem Kemeilipoor aptly puts it, BCIs are the “internet of humans,” but it is our responsibility to ensure that we do not lose sight of what makes us human in the pursuit of technological advancement.